What inspires you to write poetry?

Sometimes a poem owes its gestation to an event or to something I’ve read, e.g. the poem Sema is a response to a touristic performance of the Sema I attended some years ago in Istanbul and The Last Caliph is a response to the Turkish republic’s abolition of the Ottoman caliphate. Other poems have their origin in or allude to the spiritual journey, e.g. some of the poems in On Big Heart Mountain, The Hidden Work of Birds, and How to Think of Cancer. Sometimes I see something in or have an experience of the natural world and some words come into my mind and I work with those words to see if I can create a poem. Often I just repeat those words to myself and wait for other words to join them. Obviously Islam plays an important part in my poetry and I do frequently make references to the Qur’an and Rumi, but I tend to avoid hyperbole when I’m writing about spiritual experiences as I don’t want to convey a false sense of my spiritual life. I’m trying to realize a deeper surrender to Allah Ta’ala, that is all. What happens as a result of that unfolds naturally without having to think about it. I don’t have to write about spiritual experiences to make sense of them but I do have to write about them if I want to share them.

Do you change your poems as you write them or after you have finished?

Both. There’s a lot of changing to find the right words and rhythm. Usually I sit and observe them or reread them until something more satisfactory emerges. I’m never mentally exhausted by the editing process and sometimes I’m surprised by the finished product and barely recognize myself as the writer. I can therefore unashamedly say I often enjoy reading the finished poem. I’m not sure if this is a common feeling among creatives. Oddly enough, recently I read an interview with the Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, whom I admire, in which he says he never looks at the final product and didn’t care much about it. In fact, he went so far as to say it was just a corpse to him. I can’t imagine having such an attitude towards my writing.

I find it interesting that you were a student of Buddhism and a practicing Buddhist who gave up your study and practice of Buddhism and became a Muslim. I know you mention this in the book’s preface but could you say a bit more about this?

It’s a long story but I’ll attempt a summary. One day when I was a Buddhist I was walking down the street in Glasgow practicing mindfulness and a voice in my head quite out of the blue said something to the effect that I should look for a way that brought my soul to life. After I heard that voice I started to look for another path while still practicing Buddhism. Quite quickly I found Subud and after some months began (in January 1972) doing the latihan kejiwaan (spiritual exercise) of Subud in addition to the 100,000 prostrations to the Buddha, Dharma and Sanghaa, the meditations and puja taught to me by the late Akong Rinpoche at Samye Ling Tibetan Centre in Dumfries. I began to practice the latihan the recommended twice a week with a group for half an hour each time and after perhaps a few months began to sob intensely during the latihan because of a profound sense of having wronged my soul. I also underwent periods of intense purification. That was really the beginning of my spiritual journey.

In September 1973 I began postgraduate studies at Aberdeen University. One morning in my student flat in Aberdeen I sat down to do my visualization and mindfulness meditations (I had already by that time completed 100,000 prostrations) and found it impossible to do them. It’s hard to explain. It wasn’t that I had lost interest. I just had no ability to do the meditations. After a while I stopped trying to do them but I still practiced the puja as I still considered Buddhism to be my religion. Then I was unable to do that and I also stopped reading about Buddhism. Perhaps because I had been brought up in the Roman Catholic faith and had practiced Buddhism I felt drawn to practice a religion as well as the latihan, as the founder of Subud recommended. I thought of rekindling my Roman Catholic faith and started to visit Pluscarden Priory in Elgin to talk to one of the monks and think things over but I couldn’t accept Catholic doctrine. The founder of Subud, Bapak Muhammad Subuh Sumihadiwijojo, often spoke about the Prophet Muhammad in a unique and refreshing way that focused on the Prophet’s spiritual life and his relationship with God. He also said that Muhammad was the final prophet. I had never considered Islam as a possibility for me but both of these things somehow touched me and ultimately it became clear that accepting Islam was the obvious and natural next step to take. I have never regretted that for a moment even though after I accepted Islam I was confronted by many unattractive interpretations of Islam and not a few overbearing Muslims.

Did you read a large variety of poetry before you discovered the East Asian poets or did your interest in East Asian poetry simply stem from your interest in Buddhism?

I studied English literature in my first year as an undergraduate and had a strong extra-curricular interest in various contemporary British and American poets. So I had read a lot of poetry. But it wasn’t until I became interested in Buddhism that I discovered the East Asian poets, initially Basho and other haiku poets. I first read Gary Snyder’s translations of twenty-four of Han Shan’s Cold Mountain Poems which he translated when he was at graduate school and subsequently were published in the Evergreen Review in 1958. I came across them quite serendipitously when I was excavating old poetry journals in the university library. Snyder’s translations didn’t really touch me for some reason. Perhaps I found the tone too colloquial and his choice of words too contemporary, e.g. “did drugs”, “silverware and cars”, “hung-up mind”, but when I read Burton Watson’s more literary translations years later I fell in love with Han Shan’s poems. Watson translated one hundred poems of Han Shan and gave a much more rounded picture of the poet. I felt there was an overwhelming feeling of the fragility and brevity of life in Watson’s translations and I was not surprised to learn that he had recited some of his translations of Cold Mountain poems at his father’s funeral. After discovering Han Shan I started reading mainly anthologies of East Asian poetry.

I preferred the East Asian poets to others mainly because of their directness and their brevity as well as their sensitivity to nature and the fragility of life. I never found any Muslim poets that affected me in the same way and so continued to read Han Shan and other East Asian poets even after I had accepted Islam. The only Muslim poet that made a big impression on me was Rumi. I read him as someone who gave an enlightened view of Islam and who expressed its inner dimension, something that the latihan was beginning to impress on me. Although there are similarities between the worldviews of Islam and Buddhism there are also definite differences. I began to read the East Asian poets through the eyes of a Muslim and it became easy to appreciate them in a different way without the Buddhist terminology the East Asian poets used being a barrier. In some cases Buddhist concerns and Islamic concerns are the same, e.g. the need to free ourselves from getting too entangled in the material world and the fleetingness of life, but in other cases I simply understood many of their poems to be about signs in the Qur’anic sense or to be symbolic of the spiritual journey. Hence the group of haiku in my book is titled Signs of the Unseen.

Later on I began to use various East Asian poetic forms and to draw on East Asian influences to write poems expressing the Islamic worldview. The first poem I consciously wrote that was influenced by East Asian poems I had read was After Ramadan which expressed the kind of sadness that I felt in Chinese poems. These poems usually expressed a longing for a person or a place that the poets were apart from whereas After Ramadan was about the sadness we can sometimes feel because the fasting month has ended. After that I wrote the haiku that are in the book and sometime later the haibun. Some of the poems in the book are of course American style free verse poems and not related to East Asian writing. I don’t usually like poems that rhyme and anything I attempt feels too stiff and formal, and often ridiculous. So I stick to free verse.

Who are your favourite poets or writers, of any kind?

I don’t read much poetry these days and in fact haven’t for years. Rumi in translation is definitely the favourite, although I prefer to read the work of those translators who don’t elide Rumi’s Islamic focus. Most of my reading is simply for relaxation and that usually involves reading crime fiction in which the solver of the mystery is from Edinburgh or Venice or is a monk, a nun or a Navajo! I don’t these days read much Islamic literature. I tend to agree with Shaykh Mūlay al-ʿArabi al-Darqāwi when he says, “It is not necessary for you to go deeply into [formal religious knowledge], but rather to go deeply within and to oppose your passions.” I prefer to keep things simple and practical much like the Islam of the first Muslims. I leave scholarship to the scholars. The only Sufi books, apart from Rumi’s, that have given me any pleasure in the past ten years or longer are the primary texts, albeit in translation, Ibn Atāʾillah’s The Book of Wisdom and Letters on the Spiritual Path by Mūlay al-ʿArabi al-Darqāwi.

I’m no longer a voracious reader of East Asian literature either, but l like to read it from time to time. I feel haiku and tanka have to be read differently from other poetry. If you read too many of them in one sitting it’s easy to miss the sense of awe that they can trigger in you. Even the haiku of the renowned Japanese haiku poets Basho or Issa lose their ability to move readers if too many are read one after the other. There are English language poets who specialize in haiku but I feel it’s kind of self-defeating to publish too many in a single collection. Richard Hughes, the American writer, enthused about haiku towards the end of his life and wrote hundreds of haiku many of which I appreciate. He couldn’t understand why his publisher or any other publisher wasn’t interested in publishing his book. If you read the book that was published posthumously I think you’ll see that a whole book of haiku simply doesn’t work. If you read or write too many haiku or try too hard they inevitably descend into cleverness or, worse, cuteness. Kerouac wrote a few good haiku but should have stopped writing them long before he did. I think I’ve written all the haiku I will ever write, but who knows. If something authentic comes along I won’t refuse. But I will draw the line at trying to write a book of haiku.

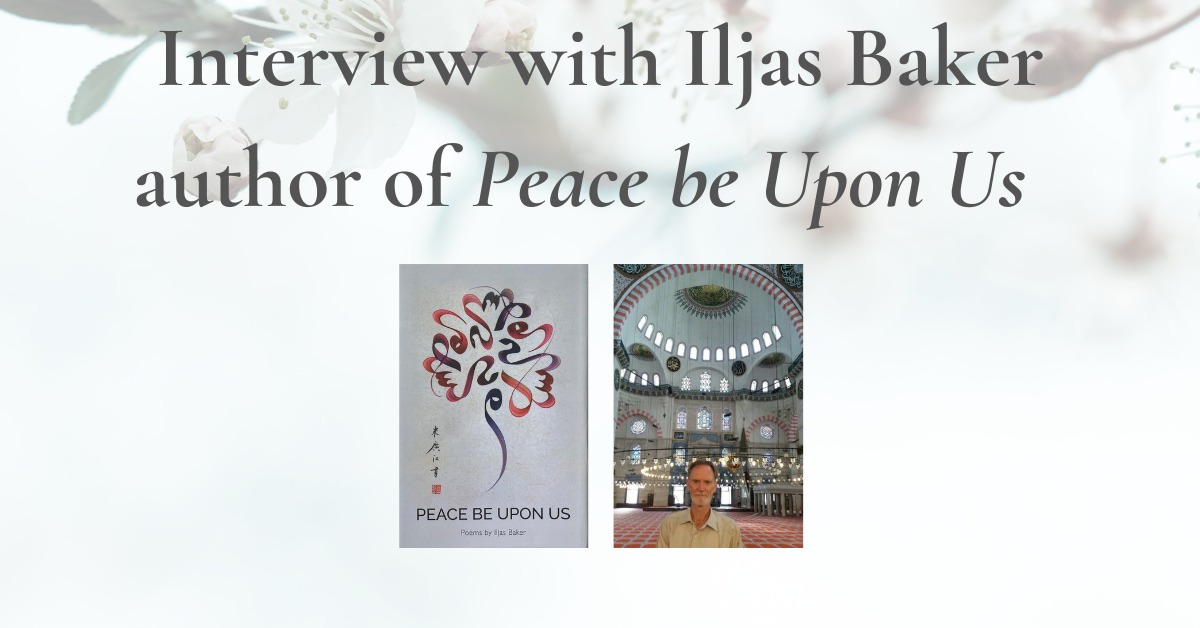

About the author

Iljas Baker was born in Scotland in 1949 and was educated at Strathclyde, Aberdeen and Edinburgh universities. He now lives in Thailand where he has recently retired from teaching at Mahidol University International College. He is married with a son and a daughter and two grand-daughters.

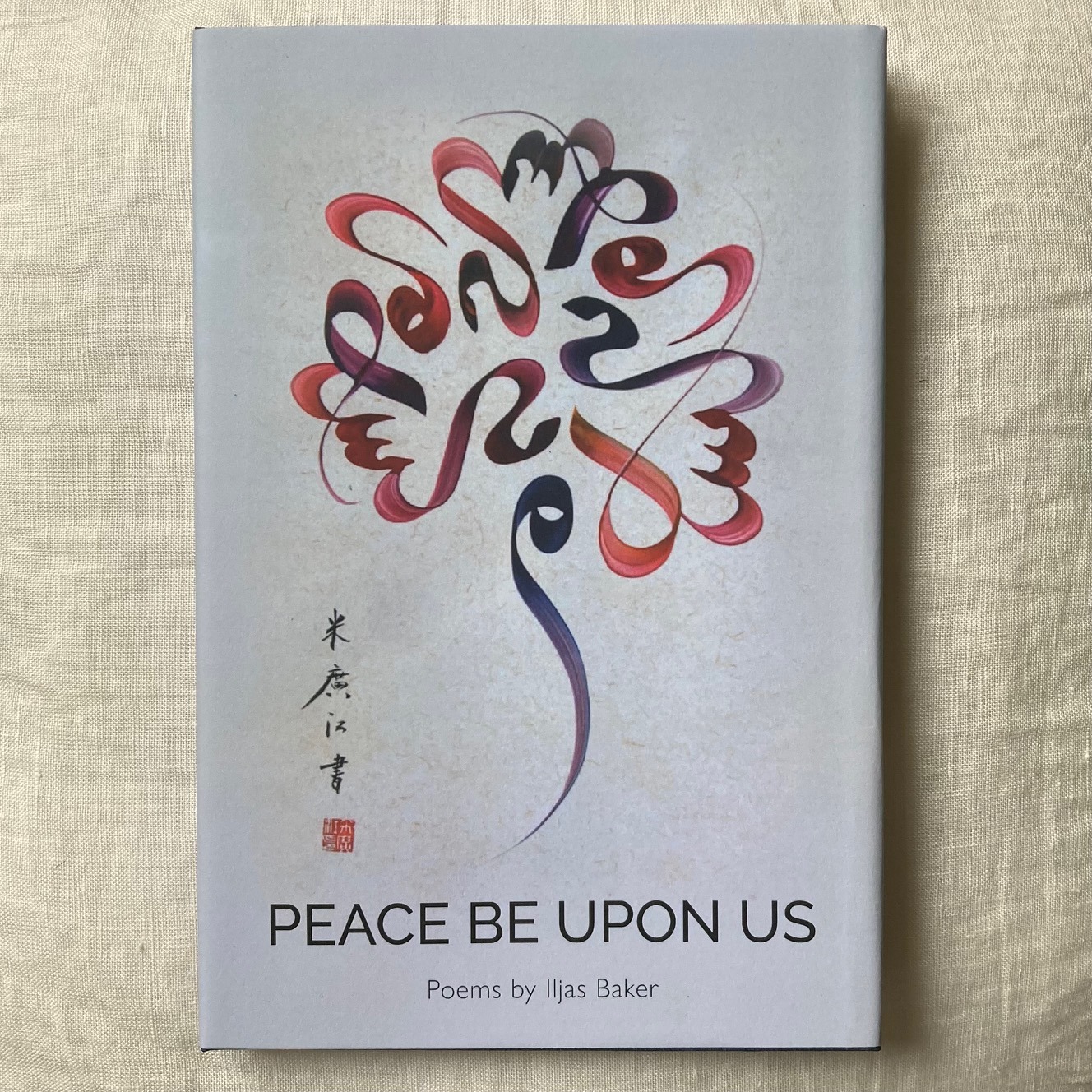

PEACE BE UPON US

“In this sublime book Iljas Baker gives us a glimpse - in poetic form - of his spiritual journey through Buddhism, the spiritual exercise of Subud, and Islam. Many of the poems use Chinese and Japanese poetical forms, especially Haiku, Haibun and Tanka, but express somewhat uniquely an Islamic rather than a Buddhist worldview. The presence of some examples of the world-famous calligrapher Haji Noor Deen's Chinese interpretations of Islamic calligraphy adds a beautiful and complementary graphic element to the subtle marriage of East Asian literary forms and Islamic spirit to be found in this book.

Iljas's poems and poetic artistry demonstrate the universality of Truth which, being Absolute, can and must manifest in every culture and in every art form, and both penetrate and embrace human life from the most mundane to the most exalted.”

-Imam Feisal Abdul Rauf, Founder and President of Cordoba House